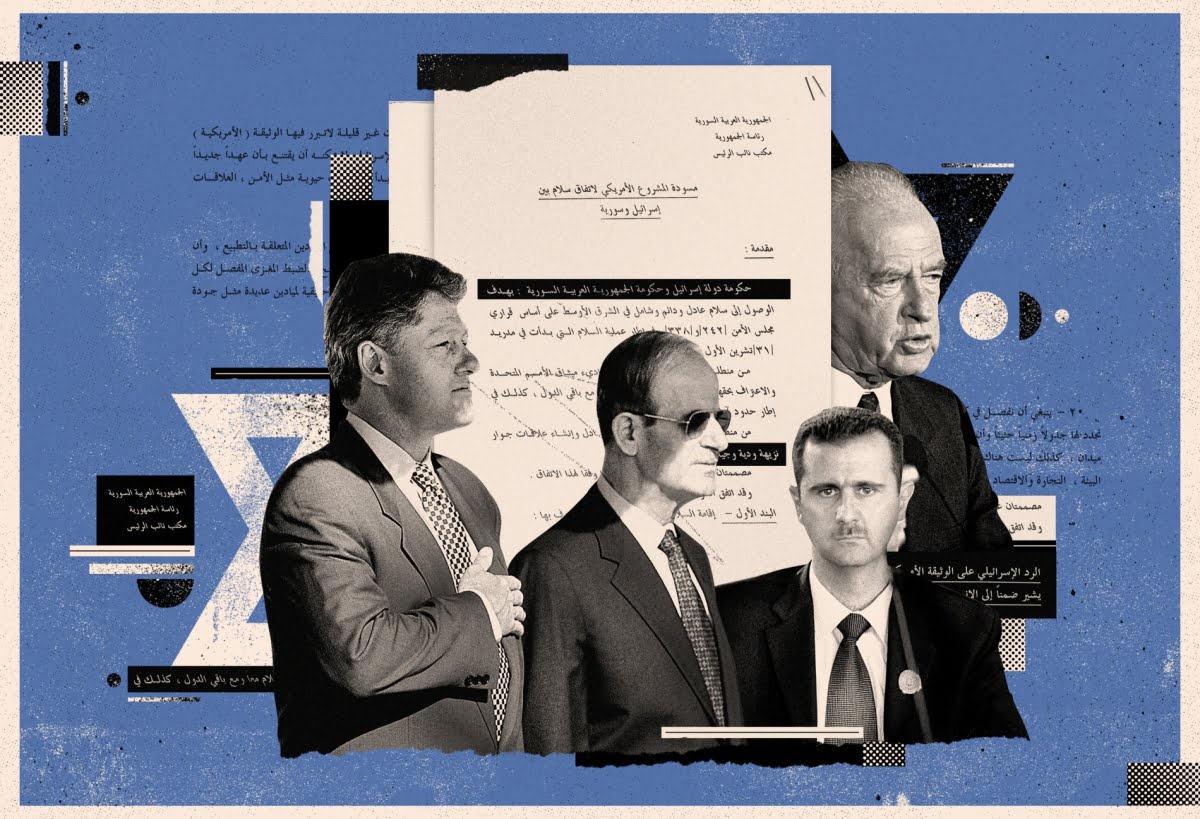

Negotiations to make peace with Israel in exchange for the return of the Golan began with Clinton but fizzled out after Hafez al-Assad died. They were briefly resuscitated under Obama but anti-government protests in Syria killed them once again.

A trove of exclusive top-level documents obtained by Al Majalla reveals how the US’s priority for Damascus shifted from normalisation with Israel to severing its ties to Iran between 2000-2011.

The Middle East and the world were watching closely 23 years ago when US President Bill Clinton met his counterpart from Syria, Hafez al-Assad.

Top-level documents prepared around the talks in 2000 have now come to light. They reveal much about a vital time of top-level diplomacy at a crucial geopolitical moment for the region and the globe.

Just 11 years later, attention returned to another testing round of diplomacy. In the 2011 push for a peace agreement, Bashar al-Assad was Syria’s president, and Barack Obama was in the White House.

Al Majalla is publishing complete drafts of key documents from both rounds of talks.

They reveal how the shift in world politics altered Washington’s main ambition over those years. The US moved from trying to persuade Syria to fully reset relations with Israel – seeking what is referred to as “complete normalisation” – to asking Damascus to sever its alliances with Iran and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

That change and what it reveals about international political currents continue reverberating through the region. It preceded the withdrawal of Syrian forces in 2005, and the obvious consequences remain today. The documents looked at in this article and the history they helped make, tell an important story about turbulent times, then and now.

The documents looked at in this article and the history they helped make tell an important story about turbulent times, then and now. They reveal how the shift in world politics altered Washington’s main ambition over those years.

The push for peace

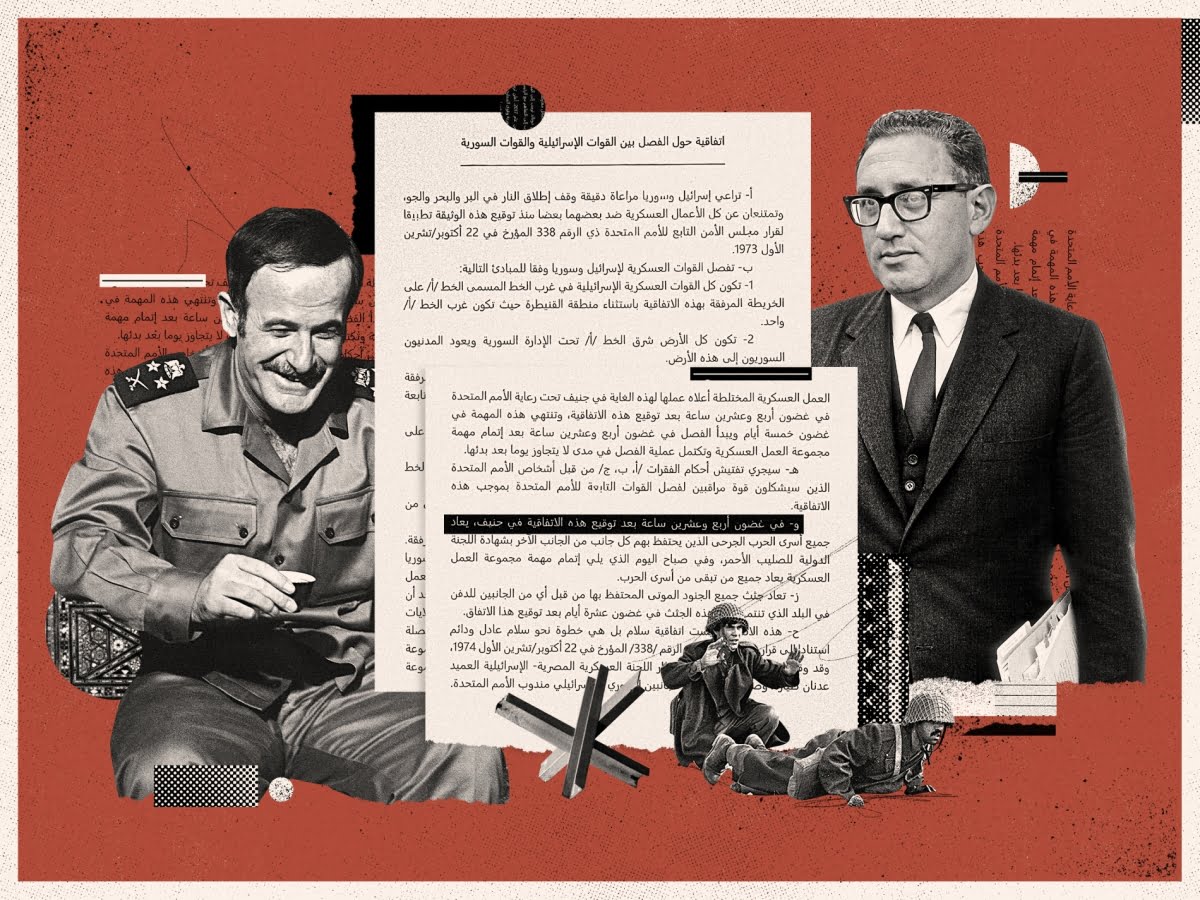

A broader peace process including talks between Syria and Israel began in 1991, at what became known as the Madrid Conference.

Negotiations were held both in public and private. They were broad and covered politics, security and military dimensions. They went on to take place in several other European venues and the US.

A pivotal moment occurred in 1993 when Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin committed to completely withdrawing from the Golan Heights, which had been occupied since 1967. In exchange, he sought normalised relations and the implementation of security agreements.

This offer became known as “Rabin’s Deposit”. It was made to President Hafez al-Assad via US Secretary of State Warren Christopher.

There was then a period of stagnation, attributed to the Oslo Accords of 1993 and the 1994 Jordanian Wadi Araba Agreement. Then came renewed US initiatives, aimed at Syria, which coincided with a change in Israeli leadership.

These negotiations were based around what became known as the Four Pillars, agreements that were strong enough to support broader moves toward peace on both sides.

The pillars were:

-

Israel’s withdrawal from the Golan Heights

-

Improved security arrangements between the parties

-

The normalisation of diplomatic relations

-

The setting of a timetable for the peace agreement

In late 1994 and mid-1995, the Syrian Chief of Staff, Hikmat al-Shihabi, reached an understanding with his Israeli counterparts – Ehud Barak and Amnon Shahak – regarding the fundamental security principles between the two nations.

The aim was to establish a balanced and mutually beneficial security framework. But critical information on the talks was leaked by Ehud Barak, seemingly as a tactic to exert pressure on Rabin.

Negotiations continued throughout Benjamin Netanyahu’s leadership from 1996 to 1999. When Israel’s Labour Party won the elections, and Ehud Barak assumed office, President Clinton revived his push for a peace accord with Syria.

Clinton’s renewed diplomacy coincided with two key factors: the deteriorating health of Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and the preparations for the succession of Bashar al-Assad to assume the mantle of leadership.

Rabin’s Deposit helps secure high-level talks

In December 1999, Clinton hosted face-to-face discussions between Ehud Barak and Syria’s Foreign Minister Farouk al-Sharaa, facilitated by US Secretary of State Madeline Albright.

It was a historic encounter and the highest-level meeting between Syria and Israel, although the chiefs of staff of both nations had held public and private meetings in late 1994 and mid-1995.

Al-Sharaa and Barak reiterated their profound commitment to achieving peace. The Syrian delegation emphasised the paramount importance of Israel’s adherence to the Rabin Deposit, originally conveyed to President al-Assad via Secretary of State Christopher in 1993.

The specific details of the Rabin Deposit included the “acceptance of withdrawal beyond the 4 June lines.” Al-Sharaa also sought a clear commitment to a security document previously agreed as part of Syria’s moves toward peace and normal relations with Israel.

In contrast, Barak primarily concentrated on security and Israel’s determination to link withdrawal with a new, deep form of peace.

There were discrepancies between the sides over the proposed timeline. Al-Sharaa advocated a shorter period, while Barak preferred a two-year implementation.

Clinton’s renewed diplomacy coincided with two key factors: the deteriorating health of Syrian President Hafez al-Assad and the preparations for the succession of Bashar al-Assad to assume the mantle of leadership.

Positive atmosphere

Even with such disagreements, there was no tension in the discussions. Both sides were content with the progress made at the ongoing talks in Washington. The positive atmosphere and the momentum achieved led to more US-sponsored negotiations in early January 1995, in Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

President Clinton kickstarted the negotiations himself.

Concerned at the potential for discussions to become stalled and keen to keep the positive momentum, the US proposed that committees, or working groups, be set up to address the key points of contention between the sides.

They met concurrently, and each one looked for ways to reach a consensus. Taken together, the committees could open the way for full agreement. There were four of them:

1. Boundary Demarcation Committee for the 4 June 1967 Line

2. Equal Security Arrangements Committee

3. Peaceful Relations Committee

4. Water Committee

For one of them, there was an inauspicious start. Israeli members of the Boundary Demarcation Committee did not show up at the designated start time, provoking a crisis. It did meet subsequently, but this working group did not make substantive progress. And the others did not create a consensus.

It was enough for an impasse. In reaction, US diplomats drew up a document to summarise the position of both sides, covering the full scope of the working groups.

Full text of document:

The Government of the State of Israel and the Government of the Syrian Arab Republic

In pursuit of a just, enduring, and all-encompassing peace in the Middle East, anchored in United Nations Security Council Resolutions 242 and 338, and in accordance with the peace process that commenced in Madrid on October 31, 1991, and in light of their reaffirmation of unwavering commitment to the principles and objectives enshrined in the United Nations Charter and the recognition of their rightful obligation to coexist in peace alongside one another and with all other nations, within mutually acknowledged and secure boundaries.

In the spirit of mutual respect and the advancement of equitable, amicable, and neighbourly relations, the two nations, Israel and Syria, are resolute in their determination to forge a lasting peace via this agreement. The key points of consensus are as follows:

Article 1: Establishment of Peace and Security Within Recognised Borders

The state of hostilities between Israel and Syria is hereby terminated, and a state of peace is formally established between the two nations. The two parties shall foster natural and peaceful relations, guided by the stipulations outlined in Article 3 herein below.

The internationally accepted permanent and secure borders between Israel “I” and Syria “S”, are as defined in Article 2 hereinafter. The precise location of these borders is a mutual accord between the parties, “S” – relying on the June 4, 1967 Line – and “I,” taking into account security considerations and other vital interests of both parties, as well as their legitimate concerns.

Israel “S” will (withdraw) “I” (redeploy) all its military forces “S: and civilians” beyond the specified borders as outlined in the attached appendix to this agreement. “S: Following this action, each party will exercise full sovereignty within their respective territory along the international borders, in accordance with the terms specified in this agreement.”

To bolster and reinforce the security of both parties, the agreed-upon documents and security measures shall be executed in accordance with the provisions delineated in Article 4 hereinafter.

The timeframe – shall set A mutually agreed-upon timetable for the coordinated and synchronised implementation of this article and all other provisions of this agreement shall be established.

Majalla

MajallaArticle 2: International Borders

The international borders separating Israel and Syria shall be delineated based on detailed maps and precise geographic coordinates. These borders are the permanent, secure, and recognised international borders between Israel and Syria, and they shall supersede any preceding cease-fire lines or borders.

Both parties shall respect these borders and the integrity and unity of the land areas, regional waters, and airspace of each other.

A joint border committee shall be formed, and its roles and operational procedures shall be outlined in the attached appendix.

Article 3: Normal Peaceful Relations

The parties shall adhere to the provisions of the United Nations Charter and the principles of international law governing relations between sovereign states in times of peace, notably:

a. Each party shall duly recognise and honour the sovereignty, geographical unity, and political independence of the other party, affirming its legitimate right to live in peace within internationally acknowledged and secure borders.

b. The parties shall endeavour to foster and cultivate amicable neighbourly relations, pledging not to engage in the direct or indirect threat or use of force against one another. Furthermore, they shall collaborate in the pursuit of regional peace, stability, and advancement and commit to resolving any disagreements through peaceful means.

Both parties shall establish full diplomatic and consular relations, including the appointment of resident ambassadors to represent each nation.

Both parties shall acknowledge the mutual advantages and benefits that arise from fair and neighbourly relations grounded in mutual respect. To this end:

a. Both parties shall strive to promote and facilitate effective mutual trade and economic ties by allowing the unrestricted and comprehensive movement of individuals, goods, and services between their respective nations.

b. Both parties shall eliminate all impediments that impede the establishment of natural economic relations, ceasing all forms of economic boycotts targeted at the other party. They shall also annul any unjust legislation and collaborate to bring an end to any economic boycott against either party by a third party.

c. Both parties shall actively encourage and promote the establishment of mutual relations in terms of international transportation between the two nations. They will collaborate to extend railway networks, facilitating natural access to ports for sailing and cargo shipping between their respective territories. They will initiate the establishment of normal relations in the realm of civil aviation.

d. Both parties shall establish natural communication channels encompassing postal services, telephone, telegraph, facsimile, wired communications, cables, television services, radio services, and satellite services between the two nations. This shall be carried out in a non-prejudicial manner, in accordance with relevant international norms and regulations.

e. Both parties shall actively seek cooperation in the realm of tourism, with the objective of simplifying and encouraging reciprocal tourism as well as attracting tourists from other nations.

Annexes and Annotations

The protocols for initiating and developing these relations shall be agreed upon. “Israel: including the timetable for reaching pertinent agreements and arrangements concerning Israeli citizens and Israeli settlements in the regions from which Israeli military forces will withdraw as per Article 1. Syria?”

Each party shall assume responsibility for ensuring that the citizens of the other party have access to proper legal actions within the judicial system and its associated courts.

1. The elements of normal peace relations necessitating additional deliberation encompass cultural ties, environmental matters, electrical connectivity, energy cooperation, healthcare, and agriculture.

2. There are other areas for consideration, including combating criminal activities and drug trafficking, cooperation against incitement, human rights, historical and religious sites, memorials, judicial cooperation, and cooperation in the search for missing persons.

Article Four: Security

A. Security Arrangements

Acknowledging the important role of security as a fundamental basis for enduring peace and stability, both parties shall take the ensuing security measures to build the bases of mutual trust during the implementation of this agreement and to address their individual security needs. The principal security arrangements are as follows: their individual security needs. The principal security arrangements are as follows:

Definition Zones for Military Forces’ Size and their Capacities shall encompass the specification of preparedness, deployment, and armament capabilities, as well as the organisations of military forces and associated infrastructure.

Within the Definition Zones for Military Forces’ Size and Capacities, a Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) shall be established. This shall encompass the territories from which Israeli forces are to withdraw and the existing Separation Zone, as defined in the accords related to the cessation of hostilities between the Israeli and Syrian armies, dated May 31, 1974, under the mediation of US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger following the 1973 conflict.

It is mutually agreed that disarmament in this zone shall be equitable on both sides of the border. As delineated in the annexe, the deployment of military forces, munitions, weapon systems, military capabilities, or military infrastructure by either party within the demilitarised zone is strictly prohibited. Only limited civilian police presence is permissible in this zone, and both parties have concurred not to conduct aircraft flights over the demilitarised zone unless special arrangements have been made.

Early Warning Systems, including an early warning station on Mount Hermon, shall be positioned with an efficient military presence. The operation of this early warning station shall be solely under the supervision and responsibility of the United States and France. The station shall be in continuous and effective operation, as detailed in the annexe.

A video monitoring and surveillance system shall be installed by both parties encompassing multinational crews and on-site mechanical equipment – through an international presence. The primary purpose of this system shall be to monitor and confirm the execution of security arrangements. Comprehensive particulars pertaining to these security arrangements, encompassing their size, location, nature, and any additional security measures, are outlined in the annexe.

B. Other Security Measures

As supplementary measures aimed at guaranteeing the total cessation of any form of hostile activities between the two parties or emanating from areas under the control of either party, both parties pledge to the following:

Each party vows not to engage in collaboration with any third party within a military-oriented alliance and guarantees that its controlled territory shall not be employed by the armed forces of a third party, including their equipment and munitions, in a manner that could adversely impact the security of the other party.

Each party commits to refraining from orchestrating, inciting, commencing, aiding, or participating in violent actions or threats of violence, of any kind, directed against the other party, its populace, or its assets.

They will take adequate measures to prevent such activities from transpiring within their own territory or the areas under their jurisdiction. They will ensure that these activities do not garner support or endorsement from individuals residing in these regions.

Each party will take all requisite and efficacious measures to forestall the entry, presence, or activities of any organisation or group, and prohibit the establishment of any structures that may pose a security threat to the other party through the use of violence or incitement to violence.

Both parties acknowledge that international terrorism, in all its manifestations, constitutes a threat to the security of nations. Consequently, they share a mutual interest in reinforcing global means to address this issue.

C. Security Cooperation and Coordination

Both parties shall establish a direct engagement and coordination apparatus, as specified in the annexe, to facilitate the execution of the security arrangements delineated in this agreement. This apparatus shall be tasked with conducting direct and timely communication regarding security concerns, reducing friction along international borders, monitoring and addressing issues that may emerge during the implementation phase, cooperating to avert mistakes or misunderstandings, and maintaining direct and continuous contact with the video monitoring and surveillance system.

Article Five: Water

Both parties acknowledge that a comprehensive resolution to all prevailing water resource disputes between them constitutes a fundamental cornerstone for securing a stable and enduring peace, founded upon relevant international principles and regulations.

They have concurred to formulate provisions that ensure Israel’s sustained access to water volumes derived from reservoirs and groundwater situated in the regions to be transferred or vacated by Israeli forces, as specified in Article One and the attached annexe.

It is imperative that these provisions encompass all requisite measures to prevent biological or chemical contamination, as well as the depletion of Lake Tiberias and the Jordan River, along with their respective sources.

To ensure the implementation of this article and the annexe, both parties shall establish a Joint Water Committee, a Monitoring and Implementation Unit, and a Joint Administrative Council. The specifics of these entities shall be outlined in the annexe.

Both parties agree to collaborate on water-related issues, as outlined in the annexe. This includes ensuring the volume and method of water allocation to Israel under other accords that pertain to water originating in Syria.

Article Six: Rights and Obligations

This agreement shall not alter – and in no circumstances shall it be construed as altering – the rights and responsibilities of both parties as delineated within the framework of the United Nations Charter.

Both parties shall commit to fully and accurately fulfilling their obligations under this agreement, irrespective of any third-party actions, and separate from any entity not encompassed by this agreement.

Both parties shall undertake all requisite actions to implement the stipulations of multilateral treaties they have endorsed in the context of their relations. This includes issuing the requisite notifications to the United Nations Secretary-General and the Secretaries of such treaties.

Both parties shall also abstain from activities that could impede the rights of either party to participate in international organisations to which they are affiliated, in accordance with the regulations governing the administration of these organisations.

Both parties pledge not to enter into commitments that are in conflict with the provisions of this agreement.

In accordance with Article 103 of the United Nations Charter, in the event of a discrepancy between the obligations of both parties under this agreement and their other obligations, the obligations delineated in this agreement shall take precedence.

Article Seven: Legislation

Both parties undertake to implement any necessary legislation to facilitate the execution of this agreement and to annul any legislation inconsistent with its provisions.

Article Eight: Dispute Settlement

Any disputes between the two parties concerning the interpretation or application of this agreement shall be resolved through negotiations.

Article Nine: Final Provisions

This agreement shall be ratified by both parties in accordance with their respective legislative procedures and shall become effective upon the exchange of their instruments of ratification, supplanting any preceding bilateral agreements between the two parties.

The annexes and appendices attached to this agreement shall constitute an integral part thereof.

This agreement shall be submitted to the Secretary-General of the United Nations for registration in accordance with established protocols.

The positive atmosphere and the momentum achieved led to more US-sponsored negotiations in early January 1995, in Shepherdstown, West Virginia. President Clinton kickstarted the negotiations himself.

After the US document was circulated, Al-Sharaa made remarks on behalf of Syria, and then Barak presented proposed amendments from the Israeli side.

Another leak sparks outcry

Elements of the potential agreement leaked. It sparked a significant outcry in both Israel and Syria, postponing the planned resumption of negotiations.

In Damascus, this was perceived as backtracking from Barak from his previous commitments regarding withdrawal from the Golan Heights to the 4 June line.

On 19 January, a leadership meeting was held in the Syrian capital to discuss the outcomes of the negotiations with the Israelis.

According to an official Syrian document, obtained by Al Majalla, Al-Sharaa stated:

“Clinton and his Secretary of State, Albright, are with us and support our position. President Clinton has entrusted me with a message for President al-Assad.”

“Barak wants peace and has requested a three-month opportunity to arrange his situation. Barak also stated that President al-Assad is the most important leader in the Levant since the emergence of Islam.”

Then, he outlined the state of the discussions as follows:

“Regarding the dispute with the Israelis over priorities, Syria wanted to discuss the withdrawal beyond the June 4 line, while Israel wanted to discuss security, water, and peaceful relations. After the US intervention, it was agreed to form four working groups. However, the committees did not reach any agreement.”

Majalla

MajallaIn messages to al-Assad, Clinton reaffirmed the US’s commitment to the Israeli withdrawal beyond the 4 June line.

Water and a line in the sand

Clinton asked the Syrian side to resolve the water issue, and only then would the 4 June issue be resolved, because Israel’s priority was water. He added that the US is ready to purchase water for Syria from Turkey.

The Syrian minister responded that the Turks would not accept, to which Clinton said: “We will pay for the water, and then no one will object.” But the Syrian minister was non-commital: “I cannot give you an answer now.” he said.

The Syrian side insisted that security arrangements should be shared equally and in parallel on both sides of the border, along the lines established in a document in 1995. And Syria refused any security measures that would affect its capital.

Elements of the potential agreement leaked. It sparked a significant outcry in Israel and Syria, postponing the planned resumption of negotiations. In Damascus, this was perceived as backtracking from Barak from his previous commitments regarding withdrawal from the Golan Heights to the 4 June line.

Lost in a map

Negotiations came to a halt, with the postponement of the working groups.

In early March 2000, in a bid to break the deadlock, Clinton called Hafez al-Assad and offered to meet in Geneva because he had “important matters” to personally convey.

Al-Assad agreed, and the meeting was scheduled for 26 March. According to a US official, al-Assad’s illness was obvious. The US coordinator, Dennis Ross, tried to touch Assad’s shoulders to assess his weakened condition.

According to another Syrian document:

“Clinton discussed the peace process and Assad’s role in commencing it at the Madrid conference. He also discussed the major regional security and stability achievements that could result from a peace agreement between Syria and Israel. Then, he presented maps to al-Assad.”

The Syrian side claimed the maps featured a strip of 200 meters along a lake.

The Syrian document added:

“Al-Assad examined the maps and identified a borderline in the Al-Bateha area along the shores of Tiberias that extended beyond the 4 June line. He also noticed a deviation in the line in the Banias area. He turned to President Clinton and said: ‘What is this? This is an Israeli map, not an American one. If this is the message you intended to convey to me, then I have nothing to say, and there is nothing for us to discuss.'”

Clinton replied: “Your foreign minister agreed to this map”.

Foreign Minister Al-Sharaa remained silent.

Al-Assad responded: “I have nothing to say or discuss. This is an Israeli map, and I will not agree to cede a single grain of soil.”

After Clinton’s departure, Al-Sharaa approached al-Assad and remarked: “Mr. President, I knew that the leader of a small nation may lie, but I never expected the leader of a great nation to do so.”

Al-Assad simply shook his head without offering a reply, according to Syrian Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam, who also stated in an official document:

“The Americans were closely monitoring President al-Assad’s health and were banking on it, believing that the president would eventually be willing to make the necessary concessions. However, the president passed away, and the national interest took precedence. He departed without compromising or conceding, without opening the door to concessions.”

Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon in May 2000, and President al-Assad died on 10 June, that same year.

His son succeeded him in power.

He turned to President Clinton and said: ‘What is this? This is an Israeli map, not an American one. If this is the message you intended to convey to me, then I have nothing to say, and there is nothing for us to discuss.

HAFEZ AL-ASSAD TO BILL CLINTON

Bashar al-Assad and Iran

After President Bashar al-Assad assumed office, fresh attempts were made to reach an agreement with Israel.

One of the most prominent occurred during a period of diplomatic isolation, which followed the assassination of Lebanon’s Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

Turkey mediated between 2007 and 2008 and proposed arranging a direct meeting between al-Assad and the former prime minister, Ehud Olmert.

After Syria’s diplomatic isolation waned, the Obama administration renewed its interest in a potential settlement.

Senator George Mitchell was appointed special envoy, with Fred Hoff as his deputy.

Hoff was the diplomat who defined and drew the 4 June line, and he was dedicated to the peace process from April 2009 to mid-March 2011. He shared his experiences in a book, Reaching for the Heights: The Inside Story of a Secret Attempt to Reach a Syrian-Israeli Peace.

In 2010, following reconnaissance visits to Damascus and Tel Aviv by Mitchell and Hoff, they travelled back to the Syrian capital in September to seek al-Assad’s approval for more diplomatic work. The aim was to make progress via the Rabin Deposit, the offer to withdraw from the Golan Heights to that line Hoff had drawn on the map.

This fresh approach explicitly took on regional detail, including Syria’s relationship with Iran and Hezbollah.

Beforehand, there had been warm words for al-Assad from senior US figures. John Kerry, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman, spoke of: “al-Assad’s openness to a peace agreement meeting all Israeli requirements in exchange for a full Israeli withdrawal to the 4 June line.”

But Washington had growing concerns about weapons, specifically the “delivery of Scud missiles to Hezbollah”. At the same time as promoting peace, the US sought to disrupt the Syrian-Iranian connection.

John Kerry brought a draft letter prepared for al-Assad to sign. This letter was based on Hoff’s discussions with the Israelis and was intended to be conveyed to Obama.

The letter included the following:

A peace treaty between Syria and Israel, which encompasses borders that reflect Syria’s complete recovery of the territories it lost in June 1967, shall result in the cessation of all Syrian support for activities, policies, and cooperation that pose a threat to Israel’s security, whether by states or non-state actors.

The peace treaty shall bring an end to the conflict between Israel and Syria and shall resolve all claims arising from events preceding the agreement.

This shall lead to a diplomatic normalization of relations, including the opening of embassies.

Syria’s relations with both state and non-state actors will fully adhere to its treaty obligations and commitments to Israel, as specified, to the mutual satisfaction of both parties.

In the event of achieving a peace treaty with Israel, Syria, in line with the Arab Peace Initiative, will provide full support and cooperation for achieving comprehensive Arab Israeli peace.

This includes securing peace agreements between Israel and the Palestinians and Israel and Lebanon, leading to the normalisation of relations between Israel and all members of the Arab League.

In 2010, Mitchell and Hoff went to Damascus to seek al-Assad’s approval for more diplomatic work. The aim was to make progress via the Rabin Deposit, the offer to withdraw from the Golan Heights to that line Hoff had drawn on the map.

This offer was seen as an American update to the Rabin Deposit.

The Syrian side attempted to secure a written commitment from Obama, including a complete Israeli withdrawal from the Syrian Golan Heights to the 4 June line.

Kerry said to al-Assad:

“I have confirmed with the Vice President (Joseph Biden) that the United States’ position necessitates the full return of the Golan to the 1967 line.”

American draft proposal presented

On 27 February 2011 – after the outbreak of protests that became the Arab Spring – Hoff arrived in Damascus to meet with al-Assad the following day.

The US envoy presented a proposed draft of a Syrian-Israeli agreement to al-Assad, accompanied by footnotes.

Full text of draft:

This agreement (Possible Framework Agreement/Prospective Peace Treaty) shall end the state of war between Syria and Israel, and establish peace. It requires actions from both parties to establish a bilateral relationship and relations with all other relevant parties, consistent with this new reality.

Accordingly, neither party, in accordance with principles of international law and the United Nations Charter, will threaten, directly or indirectly, or support any actions, efforts, or plans by any state or non-state party that threaten the security or safety of the other party or its citizens, particularly when this Agreement enters into force.

Both parties shall refrain from making any threat or resorting to the use of force, directly or indirectly, against each other. They commit to resolving all differences and disputes between them through peaceful means.

Both Parties shall terminate and prohibit any activities on their respective territories or by their nationals that assist any regular, irregular, or paramilitary forces seeking to harm the other or its nationals. (Footnote No. 1).

Neither party shall exercise its rights under any treaty or agreement with any party, regardless of whether that party represents a nation, for the collective use of force against the other party. They shall not consent to any request for assistance involving the threat or use of force against the other party, as outlined in such a treaty, agreement, or commitment. Furthermore, both parties shall refrain from participating in or maintaining participation in a hostile alliance against the other party (Footnote No. 2).

Majalla

MajallaNeither party shall transport weapons or military equipment to Lebanon or allow such activities to take place through its territory, except those intended for the official security forces of the Lebanese government. (Footnote No. 3).

Both parties share the goal of achieving comprehensive Arab-Israeli peace. They understand that this requires the conclusion of peace agreements between the Palestinians and Israel, Lebanon and Israel, and the normalisation of relations between Israel and all members of the Arab League. Both parties shall spare no effort to achieve this goal.”

Marginal Notes and Clarifications:

In practical terms, considering the prevailing policies of these entities, Syria should abstain from extending military and financial aid, encompassing weaponry, dual-use resources, training, and intelligence data, to Hezbollah, whether within Syrian or Lebanese territory, as well as to Hamas and other Palestinian factions involved in the planning, endorsement, or perpetration of violence against Israel and Israeli individuals.

Syria should also deport any individuals linked to these groups or any other organisations employing Syrian territory for restricted activities, relocating them to countries other than Lebanon.

Syria reportedly has collective security agreements with Iran, Hezbollah, and certain factions within the Arab League, which could potentially fall under the purview of this stipulation.

For instance, Syria should discontinue its affiliation with the Iranian Revolutionary Guard, including the Quds Force, and obstruct the passage of their personnel and equipment through Syrian territory or airspace. Furthermore, Syria should annul any agreements that permit the threat or application of force against Israel and Israeli citizens, should such agreements be in place.

As a result, Syria will be required to cease its engagement in all arms and military equipment transport operations, encompassing dual-use materials, destined for Hezbollah, whether within Lebanon or to Lebanon. Syria should also assist in halting the influx of weaponry to Palestinian groups in Lebanon and contribute to endeavours aimed at their disarmament.

I have confirmed with the Vice President (Joseph Biden) that the United States’ position necessitates the full return of the Golan to the 1967 line.

JOHN KERRY TO BASHAR AL-ASSAD

According to Hoff’s account of the meeting in his book, Al-Assad wanted a deeper understanding of the five main points.

The Syrian president pointed out that Lebanon was explicitly named in the proposal. Al-Assad asked if it was suitable to explicitly mention another country in the text of a Syrian-Israeli peace treaty.

Al-Assad went on to discuss all aspects of the document, including the footnotes.

He was quoted as saying:

“Everyone will be surprised by how quickly Hassan Nasrallah, the Secretary-General of Hezbollah, will adhere to the rules as soon as Syria and Israel announce a peace agreement.”

Hoff’s account:

“I told him that I would be among the most surprised individuals and asked the president how he could be so certain, considering Nasrallah’s allegiance to Iran and the Iranian Islamic Revolution.”

“Al-Assad then began to explain that Nasrallah is of Arab descent, not Persian, and underscored the importance of Syria and Lebanon being integrated into the Arab-Israeli peace process, as Lebanon’s path is contingent on Syria.”

Additionally, he characterised Hezbollah as:

“The sole true Lebanese political party, highlighting that it represents the largest sectarian faction in Lebanon, the Shi’ites, and is a capable institution with the potential to assume a leading role in Lebanon’s domestic politics.”

The conversation was detailed. It covered the Shebaa Farms case in southern Lebanon, which Beirut asserted as Lebanese territory and Hezbollah aimed to regain following Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 2000.

Hoff asked whether al-Assad’s vision of Nasrallah’s departure from the resistance movement would necessitate that Syria return the Shebaa Farms to Lebanon once Israel withdraws from the Golan Heights.

Al-Assad indicated that, according to maps, it was considered Syrian territory. He did acknowledge that potential adjustments with Lebanon could occur in the future, but he maintained that the disputed land was Syrian.

He also spontaneously said that “Syria has never been an Iranian client state,” emphasising that the peace agreement with Israel was a Syrian affair and not an Iranian one.

Al-Assad added, “he had not informed Iran when Turkish mediation efforts for a peace agreement commenced.” According to the transcript, al-Assad told Hoff, “Syria also has a public opinion, and Syrians must be convinced that their land has been fully reclaimed.”

Hoff departed Damascus with a sense of optimism.

But on the streets of Syria, the mood was very different. Protests were intensifying, and security forces were cracking down.

That prompted the US to suspend mediation.

Hoff departed Damascus with a sense of optimism. But on the streets of Syria, the mood was very different. Protests were intensifying, and security forces were cracking down. That prompted the US to suspend mediation.

From crackdown to breakdown

Then, in March, Mitchell resigned as special envoy for Middle East peace. Later in the same month, Obama hardened the US position in a speech at the State Department, saying: “Al-Assad must lead Syria to democracy or step aside.”

In August, the US president went further, saying: “The time has come for al-Assad to step down.”

As for Hoff, he transitioned from his role on the Middle East peace team to providing counsel on the crisis in Syria to the Secretary of State and the Bureau of Near East Affairs.

Today, Syria is divided into three fragmented regions, each hosting the military forces of different nations, including the US, Russia, Iran, Turkey, and Israel.