A year before the US invasion of Iraq, senior US officials worked through possible post-Saddam scenarios with Iraqi Kurds

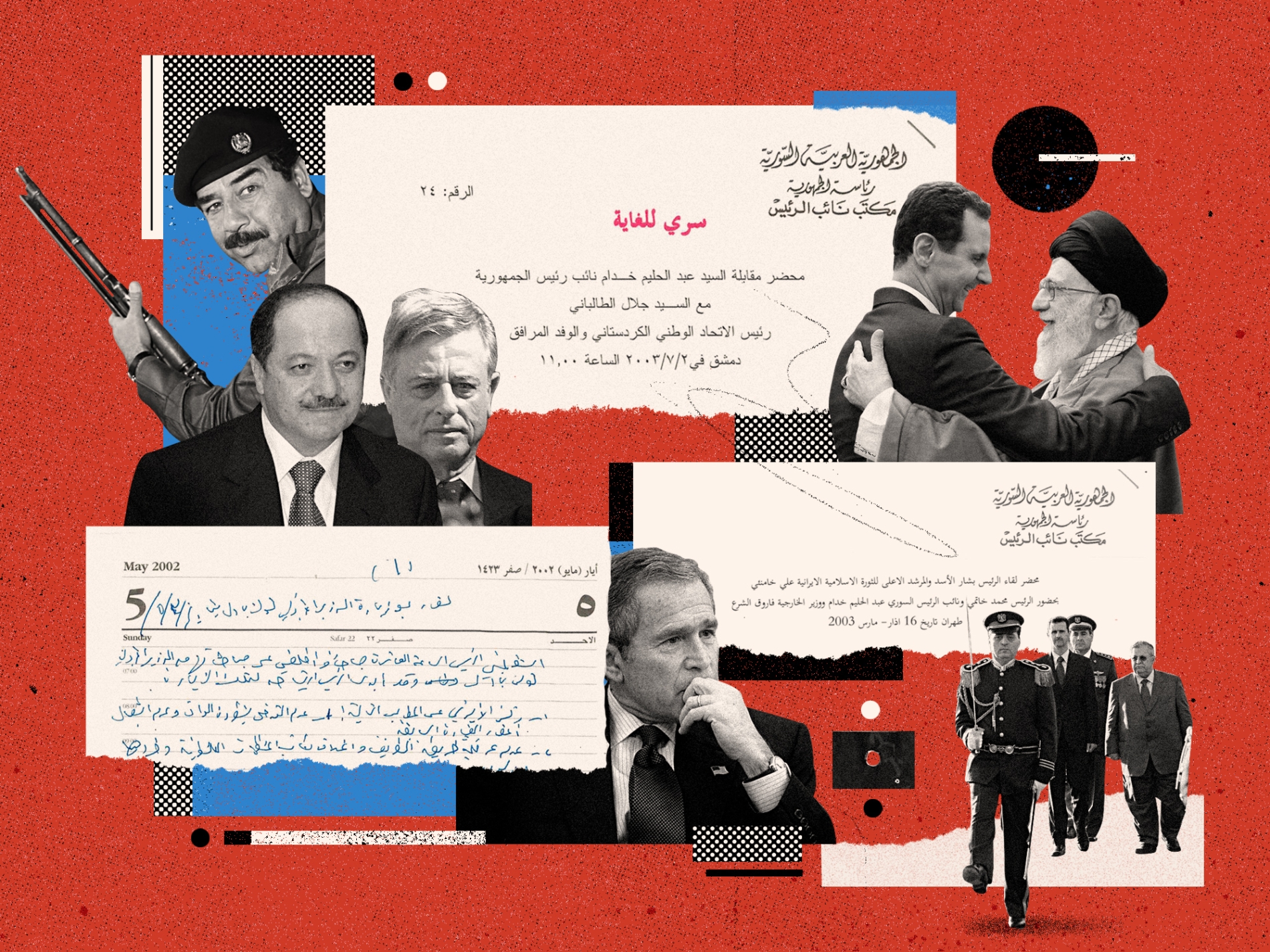

When Syria’s former Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam left for Paris in 2005, he took reams of papers, reports, notes, and files with him.

For decades, Khaddam was a trusted insider to the al-Assads. The documents give a rare insight into the heart of government from his first-hand accounts. He died in March 2020.

Among the more intriguing geopolitical periods of his time in power was the year leading up to the United States invasion of Iraq in March 2003.

In the months before, the Americans had been working closely with the Kurds in Iraq’s north. The Kurds were certainly no friends of Saddam Hussein and wanted him gone as much as Washington did.

Two of the key Kurdish leaders were Jalal Talabani of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and Masoud Barzani of the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). Talabani had good relations with Khaddam in Damascus.

Among other things, the ‘Khaddam Cache’ reveals a trip Talabani made to see Khaddam, bringing news of American plans and offerings.

Although it was already known that Talabani and Barzani had been working with the CIA, Al Majalla reveals for the first time the conversations that would have such a lasting impact on the Middle East, the effects of which are still felt today.

AFP

AFPKurdish leaders Jalal Talabani (right) and Masoud Barzani speak to the press in Dokan, northwest of the city of Sulaymaniyah on May 3, 2009.

Three years earlier

Khaddam hosted Talabani on 9 July 2000 after the latter’s return from Washington, where he was warmly received by Al Gore, who served as President Bill Clinton’s vice president.

Talabani conveyed to Khaddam that Gore “told me that he would give us the key to Baghdad and that America would work with us to overthrow Saddam Hussein and free Iraq from his rule”.

Three years later, shortly after the invasion, Saddam and his regime were gone.

Talabani later became Iraq’s president in 2005, his appetite for power having been clear for a while. He remained in post until 2014 when he became seriously ill.

Meeting Khaddam in 2000, Talabani shared that Al Gore wanted Saddam gone. “We want to remove him, and we support the Iraqi people,” said Clinton’s No.2.

“Iraq is a great nation. As soon as they get rid of Saddam, we will work to free it from restrictions, siege, and sanctions.”

Gore reassured Talabani about safeguarding the Kurdish region, saying this went beyond party politics and had support from all sides.

“This protection will remain. This is an American plan and an American policy. This plan will continue. Even if George W. Bush wins the elections, it will remain in effect.”

Considering the future

Gore had an important condition. “The opposition is good, but it must be united,” he reportedly told Talabani.

“There are other significant forces in Iraq that must come together, so you must unite, and we are ready to support the opposition internally.”

Talabani expressed his gratitude to Gore but said, “Our aspiration is for a popular, democratic change in Iraq. We do not want to see one dictator simply replace another… We desire a transformative change.”

The Kurdish leader told Gore that there was “no concrete plan on how to enact this change,” noting that Clinton had been in office for almost eight years.

“The figure of our collective grievance remains unaltered, while the international stance towards you has increasingly soured due to Saddam Hussein’s unbroken grip on power over these years.”

Gore said: “We rely on the Iraqi people. Change must originate internally. We desire a democratic system in Iraq and aim not to replace one dictator with another.” Talabani thought that sounded positive but reserved judgment.

The future leader of Iraq met others during his US visit, telling Khaddam that “the CIA is committed to removing Saddam Hussein by weakening him through economic pressures and other means”.

Backing different horses

Talabani told Khaddam that the Agency’s “primary concern is Saddam’s successor,” adding: “They are apprehensive about any change in Iraq without a clear understanding of who the next leader might be.”

When Khaddam asked Talabani about the state of the Iraqi opposition, the picture emerged as fractured and bleak.

AFP

AFPSyrian President Bashar al-Assad (right) shakes hands with his Iraqi counterpart, Jalal Talabani, during their meeting at the presidential palace in Damascus, January 14, 2007.

First, there was the Iraqi National Congress, which was comprised mainly of Kurds. Then, there was the Iraqi National Accord movement (INA), headed by Ayad Allawi, with military and security personnel who had defected under Saddam’s rule.

In addition, there was Ahmed Chalabi, who pulled in independent figures, defecting tribal leaders, and army officers who had lost their influence.

“Congress supports Chalabi, as do the Republicans,” Talabani told Khaddam.

“It’s even speculated that Israel’s Likud party may also back him. Yet the CIA supports Allawi’s INA, providing financial assistance and maintaining an office in Jordan.”

The Americans wanted Chalabi to take on a leadership role and thought the leadership of the National Congress ought to change. “We reminded them that their pressure and actions elevated Ahmed Chalabi to his position,” said Talabani.

“They had previously coerced the Al-Wefaq group to temporarily withdraw from the media and the Central Council to exert pressure on Chalabi.”

Talabani told Khaddam that “we communicated to the Americans our belief in the necessity of opposition movements that operate internally”.

Talabani’s PUK was “integrated within all Iraqi organisations and parties, including the Dawa Party, the Nasserist Party, the Communist Party, the Arab Movement, and numerous others”, he said.

“I highlighted our meeting in Sulaymaniyah earlier this year, attended by 14 organisations and those involved in the (Iraqi National) Congress.

“I emphasised to them that if their support for the opposition was genuine, they should consider this broad-based, internally-rooted opposition as the legitimate representative presence on the ground.”

The world changes

The events of 11 September 2001 (9/11), the subsequent ‘war on terrorism’, and the US invasion of Afghanistan in October 2001 shook the Arab world to its core.

The war in Afghanistan led to rare tacit cooperation between Tehran and Washington, which was one of the factors that contributed to convincing America to invade Iraq.

During this period, Khaddam met key Iraqi opposition figures, Jalal Talabani and Masoud Barzani. Each Kurdish leader gave Damascus a different stance and different insights.

AFP

AFPSyrian Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam (right) receives Masoud Barzani, head of the Kurdistan Democratic Party, in Damascus, October 17, 2004.

Khaddam welcomed Talabani to Damascus on 13 March 2002. Less than a month earlier, on 17 February 2002, a secret American delegation had visited Iraqi Kurdistan, accompanied by a Turkish intelligence officer.

The delegation included representatives from the Pentagon, the State Department, and the CIA. It was led by John McWard, who Talabani said was “familiar to us”, since he had previously visited Kurdistan in 1995.

During the official meeting, as documented in the Syrian minutes, Talabani detailed the conversation with the American delegation.

In the presence of the Turkish officer, the Americans said they had “come to foster the reconciliation initiated in Washington between you and Barzani, following conflicts in the Kurdistan region.

“We reassure you of our commitment to your protection in case of attack and to ensuring your entitlement to the oil-for-food arrangement (the United Nations agreement with Baghdad during the siege).”

Soon after, the Americans said they wanted to see the frontline, to assess the state of the Iraqi army. The Turkish officer joined the tour, which left two Americans behind with Talabani and Barzani.

We want him gone

The conversation suddenly turned serious. “Our purpose here is to convey to you that the US has resolved to change the regime in Iraq. We’re earnest about this decision,” they told the Kurdish leaders.

“Congress, the Pentagon, and the State Department have agreed to it. However, the method of implementation remains undecided. Currently, there are two proposals. One is to deliver a decisive strike against Saddam.”

“This would cause disarray in the army, allowing a military officer to step in, seize control, eliminate Saddam, and establish a new government. The other is to collaborate with the Iraqi opposition, particularly the two Kurdish parties.”

The Americans outlined their strategy to form a Quartet Committee of the Democratic Union, the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP), the Supreme Council for the Islamic Revolution (SCIR), and the Al-Wefaq Party and rely on this coalition.

Despite considering Ahmed Chalabi, a Shiite, for a leadership role, they acknowledged a significant gap in their planning—the absence of Sunni Arab representation.

They recognised that while Al-Wefaq and the SCIR were Shiite groups and most Kurds are Sunnis, Kurds are not traditionally identified with the Sunni Arab community.

At the same time, they said: “We have proposals to discuss with you.”

The Americans wanted to know about the Kurds’ relationship with Mohammad Baqir al-Hakim, president of the SCIR.

“Through us, they conveyed two messages: one to Iran, one to Al-Hakim, expressing a keen interest in meeting him.”

They were flexible on the location, even suggesting a United Nations venue.

This “hinted at potential high-profile meetings with (Vice President) Dick Cheney and possibly President George W. Bush, underlining the importance of Al-Hakim’s role in the post-Saddam era,” said Talabani.

AFP

AFPIraqis gather in central Baghdad on February 12, 2021, to commemorate Mohammad Baqir al-Hakim (image), a senior Iraqi Shiite cleric who was killed in 2003 in a car bomb explosion in the central city of Najaf.

According to Talabani, the Americans wanted “to convey their message to Al-Hakim, stressing that his influence was crucial for ensuring peace and stability in southern Iraq, particularly in mitigating potential Shiite-Sunni civil war”.

America and Iran

The Americans told Talabani: “Our stance is not against Iran. Rather, we share a common goal with it—the removal of Saddam Hussein, akin to our mutual interest in the ousting of the Taliban.

“This is contingent upon Iran refraining from intervention in Iraq. However, we welcome their engagement through Al-Hakim, other allies, or yourself.”

On Syria, they said they were “open to fostering a friendship” and that their relationship “remains positive.”

Logistically, the Americans’ preference was to enter Iraq through Turkey, but if Turkey opposed that, they said, “We have the option to enter through Syria, although we seek to avoid direct Syrian intervention”.

As for the two Kurdish groups, Talabani told Khaddam that the Americans laid out an offer: “If you are ready to work with us, we are ready to train you and provide you with weapons.” The Kurds were wary, however.

“We told them we could give an answer now because you betrayed us before. We told them we needed to know who the alternative (to Saddam) was.

“We want a democratic alternative and for all segments of the Iraqi people to participate in governance.

“Government must be peaceful for its people and its neighbours, and we do not want a dictator to come to replace a dictator; this will not solve the problem. Iraq is multi-ethnic and multi-sectarian, and we are keen on the unity of Iraq.”

The two Americans praised their candour and outlook, then reverted to discussing Iran, a country that President Bush had recently described as part of ‘the Axis of Evil’.

According to Talabani, the Americans said: “Our goal is to put pressure on them for two reasons: so that they don’t interfere in Iraq so that we can convince them to join us at the negotiating table.”

A visit to Tehran

Talabani told Khaddam that he visited Iran and met President Hashemi Rafsanjani, Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani, and Brig. Gen. Saiffullah of the Iranian National Security Council, who coordinated with Iraq’s opposition.

Rafsanjani said Iran had “no desire for conflict with America” but nor did Tehran care to negotiate, either. Iran had declined US invites to do so for two years.

Talabani said a member of the Kurdish delegation challenged the Iranians by playing devil’s advocate, saying: “Every Friday, you proclaim ‘Death to America’ in mosques.”

To this, Rafsanjani said: “Both sides tend to exaggerate and we reciprocate. We have advised Al-Hakim, given Iraq’s unique situation, to engage with the Americans.”

Rafsanjani also cautioned the Kurds against them being exploited by the Americans.

“It’s crucial for you to leverage this situation to your advantage to avoid the introduction of another Karzai.”

The reference was to Hamid Karzai, who worked with the CIA in ousting the Taliban before assuming the leadership of Afghanistan after the US invasion.

“Our aim is for you, the KDP, the SCIR, and other allied forces to form a majority, ensuring thorough preparedness,” Rafsanjani told Talabani.

Waiting for a gap

“This way, should America take your interests into consideration, we will be equipped to fortify you. Each faction should control a region to negotiate over it, and after a period of chaos, you should be poised to take power.”

Talabani then told Khaddam how he met Al-Hakim, Saifullah, and Soleimani, the Iranian figure responsible for liberation movements worldwide.

“During this meeting, we scrutinised the situation. The Iranians advised us on the importance of unity.”

“They stressed that the opposition should encompass as many groups as possible and be ready—not necessarily to initiate an American attack—but to be prepared to capitalise on the outcome if they decide to strike Iraq.”

“They (the Iranians) oppose a military coup and are adamant about preventing the rise of a new dictator in place of the old one. They said, ‘We will assist you and supply you with weapons.’ We had a list of weapons we required.

“They prepared heavy and light arms, machine guns, Katyusha rockets, mortars, and cannons for us. A competent technical team was assigned to us.”

“Saifullah informed Shamkhani (Ali Shamkhani, the present head of the Iranian National Security Council) about a list of (military requirements) from Jalal (Talabani).

“Upon hearing this, Shamkhani exclaimed, ‘From Jalal? I will sign it right away.'”

Asked by Khaddam, Talabani admitted that the final American strategy had not yet been finalised.

“In the United States, there is consensus on regime change, but the implementation method remains undetermined.”

Reflecting on the meeting, Khaddam later noted how “Jalal spoke with confidence about the likelihood of American action against the regime, clearly indicating that northern Iraq would play a role in these operations.

“This involvement could range from the direct participation of Kurdish forces to providing security assistance or using the north as a launch pad for actions against the regime in Baghdad.”