The Assad family, which has ruled Syria since 1971, when former President Hafez al-Assad took office, is surrounded by mystery. It is natural that many analyses and reports are written and published about the secrets of the ruling composition, which has lasted for nearly 53 years. The history and mysteries of that family have been addressed by many Western and Arab writers as well as through personal memoirs. The late Syrian Defense Minister, Mustafa Tlass, revealed some of these secrets in several parts of his book “Mirror of My Life”. Since 2006, the current Deputy President of Syria, Farouk al-Sharaa, has also addressed a part of the family’s policy in his book “The Lost Narrative”.

However, what was written by the former Vice President of the Syrian Republic, the late Abdul Halim Khaddam, was particularly intriguing because he was one of the few who gained the trust of Hafez al-Assad. This trust was established since his rise to power through a military coup in 1970 against his comrades in the ruling Ba’ath Party in Syria since 1963. According to the BBC network, Khaddam was the architect of Syrian policy in Lebanon since the entry of Syrian forces into Lebanon in 1976. It was this file that ignited the dispute between him and Bashar al-Assad, the son of Hafez, who “disposed” of the old guard upon his ascent to power. Khaddam transitioned from being a loyalist to defecting from the regime, declaring that “the choice was between the homeland and the regime, so I chose the homeland because it is enduring, whereas the regime is a transient phase in history.” This led to his seeking asylum in France and relinquishing the positions entrusted to him, accusing Bashar al-Assad of threatening to assassinate former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, who was assassinated.

Authority and Security

In this context, the episodes published by “Al Majalla” magazine about the conflict between the “Assad brothers” Hafez and Rifaat Assad in the early 1980s, and their rivalry for power, come to light. Rifaat is the younger brother of the former Syrian President Hafez al-Assad. He is known as “Commander” Rifaat in Syria, “Abu Dureid” (his eldest son), the leader of the “Defense Brigades”, and the “Butcher of Hama” (northwest Syria) due to his role in the brutal suppression of the uprising against the government in that city in 1982, which resulted in an estimated death toll of between 10,000 and 20,000 people. He led a coup against his brother Hafez in 1984 and declared himself his brother’s legitimate successor after his death in 2000. He called on his nephew Bashar to step down from power in 2011, following the outbreak of the Syrian uprising.

However, in his early years, he was influenced by his older brother Hafez, who was seven years his senior, and followed in his footsteps from a young age. He joined the Ba’ath Party, and when the Military Committee of the Ba’ath Party seized control in March 1963, according to “Al Majalla”, of which Hafez was a member and “its mastermind and decision-maker,” Rifaat was in military college in Homs to be closer to his mentor, who was the commander of the Syrian Air Force, where he served alongside him. This partnership was tested during the Ba’athist comrades’ conflict in 1966, following the coup that year against the rule of President Amin al-Hafiz, which resulted in the execution of the Ba’ath Party founders at that time, Michel Aflaq and Prime Minister Salah al-Din al-Bitar, and the exile of many figures who governed Syria, according to the Syrian writer Ibrahim al-Jabain. During that period, Rifaat was tasked with “establishing a military force to safeguard the regime’s health,” thus becoming “the elder brother in the palace with his hand on the decision, and the second on the streets with his hands on the rifle, ensuring the security of Damascus.”

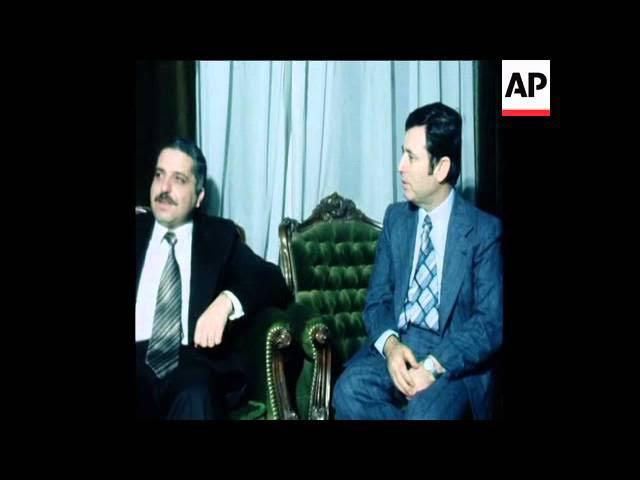

Hafez al-Assad and his brother Rifaat, with Mustafa Tlass in the middle (Al Majalla)

The period between December 23, 1973, when Assad formed his government, which lasted until 1976, was rich in events, most notably the October 1973 war against Israel and the disputes with Egypt, the severe tensions with Iraq, and the outbreak of the civil war in Lebanon. During that stage, Arab aid flowed, contributing to the launch of numerous infrastructure and industrial development projects. “Colonel Rifaat al-Assad was the focal point of communication for agents of companies eager to secure contracts in Syria,” according to documents cited by “Al Majalla” from Abdul Halim Khaddam.

Beginning of Disunity

In April 1975, after the Qatari conference of the Ba’ath Party, Colonel Rifaat al-Assad launched “directly or through an affiliated bloc” an attack on the Qatari leadership, as well as on the government, its president, and some ministers, with the aim of overthrowing Assistant Secretary-General Abdullah al-Ahmar, Prime Minister Mahmoud al-Ayoubi, Ministers Mohammad Haydar and Brigadier General Naji Jameel, and Brigadier General Mustafa Tlass, according to “Al Majalla” magazine. At that time, members of the National Leadership “requested a meeting with President Assad to inform him and alert him to Colonel Rifaat’s interference and pressure on several conference members.” During the meeting, Assad responded by saying, “Why don’t you defend the National Leadership at the conference? Why don’t you confront him at the conference?” Khaddam indicates that at that time, he was sitting far from the president. He intervened in the conversation and said, “I find this meeting surprising. You are the leadership of the party and you have decision-making power in the party. Instead of complaining to the General Secretary (Hafez al-Assad), you should gather and decide to expel Rifaat from the party and the army, thus safeguarding the leadership and the party.” Assad replied, “Indeed, why do you come and complain? Take responsibility.” Khaddam adds that in the evening session of the conference, he “strongly attacked Colonel Rifaat al-Assad” and accused him of “spreading negligence in the armed forces, corruption, and attempting to sabotage the party through alliances,” despite the fact that the man always treated him with affection and respect. Khaddam concludes, “Before I finished my speech, I turned to President Hafez and said to him, ‘You have to choose between your brother and your comrades…'”

Rifaat appointed as Commander of “Saraya al-Difaa” (Defense Companies)

After the return of security and political tensions between Damascus and Baghdad following the October War when Hafez al-Assad then refused to let the Iraqi army cross into Syrian territories, sparking rumors among Syrians that the Iraqi army did not intend to cross to fight the Zionist entity but rather to occupy the capital Damascus, subsequently leading to Iraq’s control over Syria, according to the researcher in Islamic political and cultural history Ahmed bin Saleh al-Dharrif. Following this, both armies mobilized to confront each other, and the Iraqi intelligence carried out a series of sabotage acts in Syria, as reported by “Al Majalla.” Meanwhile, on October 26, 1977, Khaddam, who was the Minister of Foreign Affairs at the time, narrowly escaped an assassination attempt at Abu Dhabi Airport while accompanied by the Minister of State for Foreign Affairs of the United Arab Emirates, Sheikh Saif bin Ghobash, as they were heading towards the exit. Gunshots were fired at the ministers, and Khaddam quickly ran to the VIP lounge before being hit by bullets. Sheikh Saif bin Ghobash was shot three times and succumbed to his injuries. The perpetrators were three individuals, one of whom was a 19-year-old Palestinian born in Baghdad. Upon returning to Damascus, he was quoted by the Middle East News Agency as saying that “the group that attempted to assassinate him came from Baghdad.” Khaddam then accused the “capital of an Arab country” of orchestrating the assassination attempt, stating that “the group dispatched by this capital to assassinate him knows well that this action primarily serves the Israeli enemy,” according to Reuters. During that period, Rifaat’s influence grew, especially after he became the commander of the “Saraya al-Difaa” (Defense Companies), an elite force consisting of 40,000 members not affiliated with the army, advancing in the party’s leadership. He expanded its activities among the youth, women, and media, and founded the “Supreme Association of Graduates” to unify university graduates.

On the dangerous front, the movement of the “Vanguard” organization emerged, led by Marwan Hadid, all of whose members belonged to the Muslim Brotherhood. They carried out several assassinations, including Major Mohammed Ghra in Hama and Dr. Mohammed Al-Fadl, the President of Damascus University. In that atmosphere, General Abdelrahman Khalifaoui assumed the responsibility of the presidency of the government and found himself in conflict with “most of the regime’s factions, especially with Colonel Rifaat, the security apparatus, most members of the Qatari leadership, and the majority of branch leaders, always being in conflict against corruption,” according to Khaddam. He adds, “This brought upon him the enmity of most of the security officials and centers of power in the armed forces, in addition to the scathing criticism from members of the Qatari leadership, sparking intense campaigns against him.” In light of this, the Qatari leadership of the ruling Ba’ath Party decided to dismiss Khalifaoui’s government, in the absence of President Assad, who “was surprised by the matter and took it lightly.” He called for a meeting to inquire about the matter, “where Assad began laughing, saying, ‘What happened in the world?’ Secretary Qatari assistant Mohammad Jaber responded with humor, ‘We were discussing government-related topics and we somehow transitioned to proposing confidence in Comrade Khalifaoui, and the leadership unanimously voted.’ Then, the President asked General Khalifaoui for his opinion, and he replied, ‘I agree with the decision and cannot continue.'” Khaddam adds, “President Assad remained silent for a while and then turned to me, saying, ‘Apparently, we have no one else but you to form the government.’ I replied, ‘I apologize for the same reasons I apologized for in 1971. My presence in the government will create significant problems for you because I will arrest some leaders due to their corruption, and this may create complex situations. I intended to form an investigation committee with some members of the leadership, including Rifaat Assad.'”

Mohammed Ali Al-Halabi, who was the President of the People’s Council at the time, assumed the presidency of the government on March 30, 1978. Khaddam writes in his documents, “In March 1978, I met with Assad, and at that time, the campaign against Rifaat was intense among Syrians. During our discussion about the situation, I said to him, ‘The campaign against Rifaat is significant, and it weakens the regime, so we must address Rifaat’s situation.’ He nervously replied, ‘Rifaat is a thorn in the eyes of the reactionaries.’ I responded, ‘In the future, we will see him as a thorn in the heart of someone.'” However, during Al-Halabi’s government, paralysis and corruption increased. In order to protect himself in his new position, Al-Halabi placed himself under the authority of Colonel Rifaat, who was his commanding officer. “Indeed, Rifaat interfered in state affairs and gave directives to Prime Minister Mohammed Ali Al-Halabi, who was not bold enough to deter him and would comply with his requests, believing that Rifaat had influence over President Hafez,” according to Khaddam’s documents.

The massacre at the Artillery School in Aleppo,

committed by Captain Ibrahim al-Youssef, an instructor at the Artillery College in Aleppo in 1979, was a crucial turning point followed by a wave of armed violence carried out by some groups affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood in response to the heinous crime. “He entered the classroom holding a machine gun and demanded that Sunni Muslim, Druze, Ismaili, and Christian students leave the room and killed about 40 of his students belonging to the Alawite sect,” according to “Al-Majalla.” This crime shook Syria and sparked a wave of violent anger among Baathists, the armed forces, and security forces, leading to the involvement of Muslim Brotherhood groups in killings and bombings. Regardless of the truth of what happened in the classroom where the horrific massacre against the students took place, the narrative closest to the truth, deeply etched in Syrian history, was that al-Youssef made sure that only Alawite students were killed. Ironically, al-Youssef was originally a Baathist officer, but the Brotherhood-affiliated “Al-Talea” organization did not hesitate to claim responsibility for the operation, while the official leadership of the group denied any connection to the attack, as well as denying its affiliation with the entire “Al-Talea” organization, according to the magazine “Hibr” in an April 2018 report.

Between December 22, 1979, and January 6, 1980, a Ba’athist conference was held in Qatar. The atmosphere of the conference was tense due to the security situation resulting from assassinations and bombings carried out by the Muslim Brotherhood on one hand, and the state’s unraveling on the other hand. Khaddam says, “It was clear from the first day that the conference was divided into two currents: one led by Colonel Rifaat, who was trying to control the conference and ensure the success of a leadership loyal to him to seize control of the party and the reins of the state. The second current was led by most members of the Qatari leadership who were concerned about Rifaat’s behavior and practices, and they were supported by the majority of civilian conference members and the majority of military members.” Khaddam adds that “Rifaat al-Assad tried to exploit the confrontation with the Muslim Brotherhood to gain the support of conference members, while the other side adopted a campaign against corruption in the state and corrupt individuals and how the country’s resources were looted, and they were protected by some centers of power in the state, and Colonel Rifaat al-Assad was the target.” At this Ba’athist conference, Rifaat stated that the time had come for a “strong response” and called on everyone to show absolute loyalty. He was quoted as saying, “Stalin sacrificed 10 million people to preserve the Bolshevik revolution, and Syria must do the same to preserve the Ba’athist revolution.” Rifaat threatened to “fight 100 wars, destroy a million fortresses, and sacrifice a million martyrs” to maintain the regime, unleashing the crackdown on the uprising between 1979 and 1982, which peaked with the shelling of Hama in February 1982. In 1983, he sent “his paratroopers” to Damascus with orders to remove the veil from women in the streets, prompting sharp criticism that led his brother to publicly condemn it, according to “Al-Majalla.”

Vice President and “Succession”

Khaddam points to a dangerous phenomenon, which is succession, and says that in November 1980, after a meeting with Assad where they discussed life, death, and the fate of the country in case of a sudden event, he decided to appoint a vice president so that the country would not fall into a void to ensure continuity. It was clear to Khaddam that he “intended to appoint his brother Rifaat, with whom he had very close ties.” “So I took the initiative to advise him not to go ahead with it, because there would certainly be a power struggle between you and the vice president you would appoint…”. In 1982, Assad surprised the Qatari leadership in the Ba’ath Party by asking each member to write down on a piece of paper the name of the person they nominated for the position of vice president, “thinking that the majority would be in favor of his brother, but he took the papers and never spoke again about appointing a vice president.”