The relationship between Presidents Hafez al-Assad and Saddam Hussein is complex and overlapping, just like the relationship between Syria and Iraq, and between Damascus and Baghdad. There are various factors at play, including partisan, sectarian, ideological, and geographical considerations, as well as a competition for leadership in the region.

The root of their rivalry can be attributed, in part, to the interdependence of the destinies of the two capitals. The Baath Party came to power in Damascus in March 1963 but lost it in Baghdad at the end of the same year. After a change in the direction of governance in Syria in 1966, the Baath Party returned to power in Iraq after two years. In Syria, Assad resolved the internal conflict in 1970.

Several attempts were made to reconcile the “Baath” regimes. Iraq indeed contributed to the October 1973 war, but the relationship soon deteriorated once again. At that time, Saddam Hussein was closely aligned with President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr, while Hafez al-Assad was consolidating his position in Damascus and Lebanon in 1976. Developments in the Egyptian-Israeli negotiations and the advancements of the revolution in Iran compelled the two countries to navigate a challenging path. In October 1978, Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr and Hafez al-Assad signed the “National Action Charter,” leading to the establishment of the “State of the Union” at the beginning of the following year, just two weeks before the announcement of the revolution in Tehran.

Among those opposed to this effort were two individuals who had aspirations for power: Saddam Hussein in Baghdad and Rifat Al-Assad in Damascus. Assad took measures to neutralize his brother, but Saddam turned against Al-Bakr, accusing his neighboring rival of “conspiracy.” He ordered the execution of pro-unity enthusiasts and eventually rose to the top of the power hierarchy in July 1979.

Assad’s attempt to strengthen the “southern front” with Israel following the signing of the Camp David Accords was paralleled by Iraq’s effort to fortify the “Eastern Gate” with Iran.

Once the Iraq-Iran war broke out after the revolution in Tehran, Assad aligned himself with Saddam’s adversary, plunging the Damascus-Baghdad relationship into a deeper rift. In response, Baghdad severed diplomatic ties with Damascus in October 1980 and provided support to the Muslim Brotherhood in Syria.

Meanwhile, Syria, deeply involved in Lebanon, closed its border with Iraq in 1982, thereby cutting off the Iraqi oil pipeline to the Mediterranean. Iran stepped in and replaced it with its own oil supply.

- A secret meeting

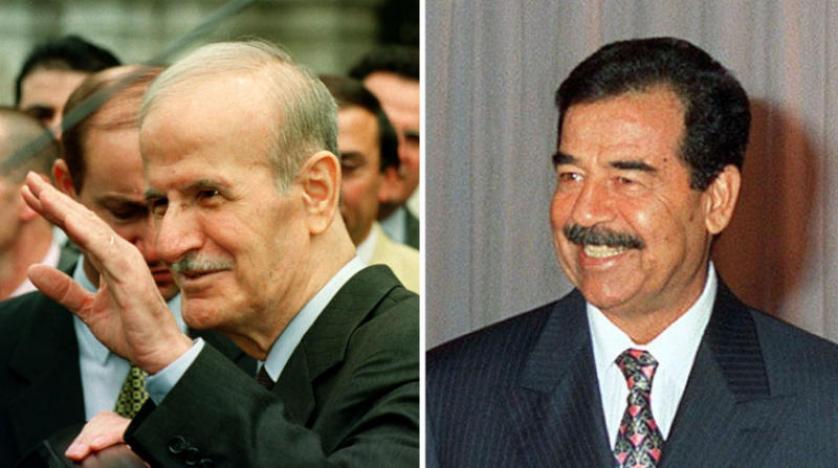

- A secret meeting took place in the mid-eighties, near the end of the Iran war, mediated by King Hussein of Jordan. It brought together Assad and Saddam in a “stormy marathon” meeting. Secret “test” meetings were held involving Farooq al-Shara, Abdel Halim Khaddam, and Tariq Aziz.

Following Saddam’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, Assad joined the international coalition to liberate it. This move strengthened his internal economic situation and influence in Lebanon, while his Iraqi opponent faced isolation and sanctions.

In the mid-1990s, the two “comrades” once again felt the need to assess their relationship. Assad sought alliances to protect himself from the fluctuating peace negotiations with Israel and to resolve the economic crisis, while Saddam aimed to lift the siege imposed on Iraq.

Both leaders were concerned about Turkish pressure, the escape of Hussein Kamel (Saddam’s brother-in-law) to Amman, and Jordan’s discussions about “federalism.” Each leader chose their closest “comrade” to establish a secret channel: Saddam appointed Anwar Sabri Abdul Razzaq Al-Qaisi, his former office manager from 1972 to 1976 and ambassador to Doha, while Assad selected Khaddam, his deputy and partner during their struggle with the “Baathist” comrades in the sixties. Saddam scrutinized Assad’s background, executions, and the alleged Syrian conspiracy. Assad also renewed attempts with secret meetings involving Aziz. The confidentiality of the discussions did not need to be confirmed to the messengers, Khaddam and Al-Qaysi, as they were loyal companions of the regime who understood the consequences of leaking information.

According to minutes obtained by Asharq Al-Awsat from Khaddam’s papers, which he took with him to Paris in 2005, and Ambassador Al-Qaisi’s interview with the newspaper, there is a difference regarding who initiated the dialogue. Khaddam states that Saddam took the first step in August 1995, and Assad responded with “doubts” due to past experiences and Saddam’s role in thwarting the “Charter of Action” in 1979.

However, Assad made the decision to continue the dialogue and subjected his Baathist counterpart to tests before moving past their estrangement. Al-Qaysi, on the other hand, believes that the initiative came from Assad when he publicly expressed concerns about Jordan’s federalism project threatening both Syria and Iraq. Assad received a signal from Khaddam to open a channel between the two key figures.

– Urgently… And slow down

In his letters to Assad, Saddam swiftly took the initiative to reopen the two embassies that had been closed in 1982, hold political meetings, and open the borders. Assad responded in early 1996 by adopting a cautious approach, ensuring not to strain the relationship between Damascus and other Arab countries. He conveyed his intention to “establish contacts with several Arab countries to avoid further complications in the Arab situation.”

Al-Qaysi informed Asharq Al-Awsat that he made six secret visits to Damascus, including four through Sudan. He emphasized that Saddam was genuinely committed to turning a new page with Assad and restoring relations. He stated, “The president instructed me to inform the Syrians that if Assad takes one step, I will take 10 steps.” The primary reason for establishing the channel, according to Al-Qaysi, was to “persuade the Syrian brothers not to receive Hussein Kamel.” Indeed, Kamel was not received due to shared concerns about the Jordanian project proposing a federation. Al-Qaysi mentioned that Saddam proposed a secret summit with Assad on the border, the formation of a “joint political leadership,” bilateral discussions to revive the “Charter of Action,” and the consideration of an Arab summit in Damascus for Iraqi-Arab reconciliation. In a letter to Assad in March 1996, Saddam wrote, “King Hussein’s recent statements before his visit to Washington confirm his hastened efforts to push the United States to conclude a military agreement and form a regional alliance with Israel and Turkey as its backbone. This is undoubtedly directed against Iraq and Syria.” Here, Mana Rashid, the head of Saddam’s special security service, revealed secret Syrian-Iraqi security meetings aimed at coordination and preventing Jordan and Turkey from exerting pressure on both countries. Al-Qaysi added that Saddam “graciously received” Assad’s criticism of the federal project.

“Abu Uday”

By analyzing meeting minutes and secret messages, it becomes evident that the dialogue between Assad and Saddam has progressed significantly. Khaddam, acting as a messenger, now conveys Assad’s “greetings” to Saddam, who reciprocates by addressing his rival as “Brother President.” Throughout their discussions, both leaders continue to navigate between various demands and possibilities.

Assad keeps French President Jacques Chirac informed about his interactions with Arab counterparts. In a message, he cautions Chirac about the worrisome situation in Iraq, describing it as a potential explosive bomb. Surprisingly, Chirac deviates from the expected conversation and brings up the topic of Syrian presence in Lebanon. He presents Assad with an offer: contribute to the disarmament of Hezbollah in exchange for Israel’s withdrawal from the Golan Heights and the assurance of Syria’s military presence in Lebanon.

During the latter part of 1996, Assad’s objective shifts towards preventing the overthrow of the Iraqi regime, as opposed to his previous intention of instigating it. To achieve this, he decides to open previously closed borders. Although initially hesitant to name Tariq Aziz as the responsible figure for developing relations due to previous unsuccessful engagements, Aziz eventually visits Damascus in November 1997. Additionally, Assad welcomes Foreign Minister Mohammed Said Al-Sahaf in February 1998.

At that time, Assad firmly believes that Saddam is consistently finding pretexts to avoid a military strike amid the ongoing crisis with international inspectors. Consequently, he concurs with Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak’s view that Saddam Hussein should be openly informed about the impending strike, which would specifically target him as the leader of the regime and the country. Assad recognizes that regime change can only be realized by directly hitting Saddam.

Once again, regional files experienced an overlap in their significance. Following Chirac’s exchange proposal involving Iraq and Lebanon, US President Bill Clinton interlinked Iraq and the resumption of Syrian-Israeli peace negotiations. This connection was established on February 21, 1998.

In a letter to Assad, Clinton expressed the importance of Syria maintaining neutrality if military action was taken against Saddam, while emphasizing Iraq’s full compliance with United Nations resolutions. Clinton acknowledged their past negotiation efforts and expressed his reluctance to start from scratch.

Assad replied on March 13, 1998, expressing concern and tension regarding the potential military action against Iraq. He emphasized the desire to resume negotiations with Israel from the point where they had left off after Shimon Peres’ loss and Benjamin Netanyahu’s victory in 1996.

Consequently, borders were opened, and an office for reconciliation was established in both Damascus and Baghdad. The transition occurred in Damascus, while the regime in Baghdad underwent overthrow. As the American attack on Iraq approached in 2003, President Bashar Al-Assad traveled to Iran and met with Ali Khamenei, the “guide.” They agreed to jointly resist the Americans in the buffer region between their countries. Over the course of 18 years, the new Iraq, which was once the “Eastern Gate” with Iran, underwent significant transformation. Meanwhile, Syria and its people, representing the “Southern Front,” reached this point after a decade of both “spring” and war.

The contents of the messages exchanged between Saddam and Assad remained undisclosed. However, the aim of revealing and confirming their validity, as stated by Ambassador Al-Qaisi, along with providing additional details, is to shed light on a significant aspect in the history of Syria, Iraq, and their regional ramifications, many of which remain incomplete.