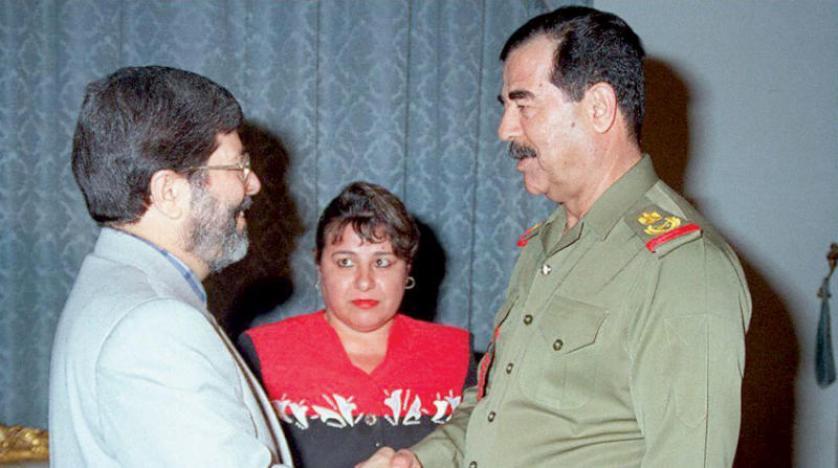

Late Syrian Vice President Abdel-Halim Khaddam and Lebanese Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri (center) sit next to former President Amin Gemayel during the funeral of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in Beirut on February 16, 2005 (Getty Images - AFP)

The third episode of the memoirs of the late Syrian Vice President Abdel-Halim Khaddam – published by Asharq Al-Awsat – discusses the relationship between Damascus and the late Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri from its beginnings in 1982 until Hariri’s assassination in February 2005.

Khaddam says that in April 1982, Hariri was introduced to Damascus at the request of Druze leader Walid Joumblatt.

“In April 1982, I received Mr. Rafik Hariri at the request of Mr. Walid Joumblatt. It was the first time I met him. All I knew was that he was a Saudi businessman of Lebanese origin.

“The meeting focused on understanding his orientation, aspirations, and his relationship with the Lebanese domestic scene. Hariri was cautious, spoke vaguely, and I felt he was trying to understand our approach to the Lebanese issue. At the end of the session, he asked to visit me again, and I welcomed him.

“The second meeting took place two weeks later. We had a lengthy discussion about the Lebanese file that lasted five hours. We had lunch at my home, where Hariri spoke candidly about his education and the circumstances he experienced, his affiliation with the Arab Nationalist Movement, and his involvement in smuggling George Habash (Secretary General of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine) out of Syrian prison.

“He also talked about his work in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, from his first job to the major projects he undertook. Regarding Lebanon, he said: ‘Lebanon is my homeland, where I grew up and where my family lives. It is part of my life, so allow me to come more often to Syria in order to find a solution to the Lebanese crisis.’

“An in-depth discussion took place about the Lebanese crisis, its causes, and circumstances. In my view, the crisis was due to two reasons: the first was Lebanon’s sectarian system, which prevented the unity of Lebanese components, while the second reason was related to the conditions of the Palestinian resistance, which found itself in conflict with political formations of a Christian character.

“We agreed on the analysis and examined ways to reach a solution. Hariri promised to present a written proposal for us to discuss.”

Khaddam recounts that Hariri presented his proposal to Damascus during their next meeting. He notes that he had some objections, as the project maintained the sectarian nature of the state’s constitutional institutions and the distribution of seats.

Hariri asserted that these problems would be resolved gradually, to which the Syrian Vice President responded: “The Lebanese constitution, drafted in the 1920s, includes a provision that stipulates the abolition of political sectarianism after a certain period; that period has lasted from 1920 to the present day. Therefore, if there is no specific and decisive moment for the transitional phase, sectarianism will persist, and the conflict the Lebanese people have been witnessing for many years will continue.”

Khaddam claims that an agreement was reached to set a specific period for the transitional phase. When Hariri presented his project to other Lebanese leaders, he received the consent of some and the opposition of others, including those who wanted to adhere to the sectarian formula.

Hariri used to visit Damascus every week, either to discuss the Lebanese national issue or to deliver messages from the late King Fahd bin Abdulaziz to President Hafez al-Assad.

After the Lebanese elections of 1992, Khaddam states that Damascus discussed all the names of well-known political figures who could assume the position of Prime Minister in the new government.

He describes how Assad “tested” Hariri before agreeing to appoint him to the position. “Suddenly, President [Hafez al-Assad] asked him: ‘If you were the head of the Lebanese government and we were in disagreement with the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, how would you act?’ Rafik replied: ‘Mr. President, I am Lebanese and I love my country, and I am also Saudi… Therefore, I cannot abandon the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia because I am not ungrateful. I am an Arab nationalist. I see Syria as the incubator of the Arabs and I can only be with Syria. Therefore, if there is a disagreement, I will work to resolve it, and if I fail, I will retire.’ President Hafez responded: ‘If you had said anything else, I would not have believed you and you would have lost my trust. I will ask Abou Jamal (Khaddam) to inform the Lebanese president that we support the appointment of Rafik Hariri.'”

“That is how Rafik Hariri became the Prime Minister of Lebanon. He committed to respecting every word he said to me as well as to President Hafez and provided great services to Syria through his foreign relations,” Khaddam said.

He notes, however, that when Bashar al-Assad took power after his father’s death, he launched a campaign against Hariri, influenced by a group of Lebanese who had previously been associated with his brother Bassel and had personal ambitions. This prompted Bashar’s friends in Lebanon to attack Hariri further.

According to Khaddam, these campaigns increased the isolation of the Syrian president on both the Arab and international levels. The man was left with only one option: to fall into the arms of Iran.

During this period, presidential elections were supposed to take place in Lebanon, but Bashar insisted on extending the mandate of President Emile Lahoud. The Muslim community, some national forces, and political currents opposed this extension.

Signs of a new Syrian campaign against Hariri appeared. This was clearly manifested during a meeting of the Progressive National Front (a coalition of parties led by the Baath), during which Foreign Minister Farouk Al-Sharaa spoke about the political situation and was asked about relations with Hariri. He replied: “He is conspiring against Syria and is involved with the United States and France against our country.”

As Syria insisted on extending Lahoud’s mandate, Hariri announced that he would resign from the government. As a result, the Syrian presidential palace summoned the Lebanese Prime Minister for a meeting with Bashar.

Seeking advice, Hariri contacted Khaddam and asked him: “What should I do? I don’t want to stay in power.” The Syrian official replied: “Continue insisting on your resignation, and if he pressures you, present him with the proposal for a Lebanese national reconciliation between all parties.”

During the meeting, Rafik took a tougher stance. Al-Assad asked him: “What are your conditions for retracting your resignation?”

He replied: “A national reconciliation meeting, a national unity government in which everyone participates without exception, the freedom to decide, and the non-interference of President Lahoud in governance affairs.”

Days and weeks passed without the government being formed. In early October, Minister Marwan Hamadeh survived an assassination attempt that heightened tensions in Lebanon.

Khaddam recounts that in mid-January 2005, the regional leadership of the Baath Party held a meeting to discuss some party issues. Assad said: “I will speak about Lebanon. There is an American-French conspiracy against us, in which Hariri is involved. This represents a danger to Syria.”

The Syrian Vice President says he received Mohsen Dalloul, who had strong relations with Hariri, the next day.

“I informed him of Bashar’s speech and asked him to inform Rafik that he should leave Lebanon immediately, as the hatred against him is great.”

“On February 14, we had a meeting at the regional command. After the meeting, I entered Dr. Ahmed Dergham’s office, a member of the leadership, and the television was on. I was shocked by the news of a large bomb explosion in front of Hariri’s convoy, on its way to the Parliament. A member of the leadership was next to me and said: ‘He has done what he talked about during this meeting.'”

“I went home feeling sad because I lost a friend who served in Syria and Lebanon… I remembered President Hafez’s position towards Hariri and how he had protected him from the campaigns of the Syrian security services… ‘The day Hariri was assassinated, I went to Lebanon and found a large crowd in front of his house. When I got out of the car, I heard someone say: “What is he doing here?” Then another person replied: “He is Abu Baha’s friend, not one of those who hate him.”