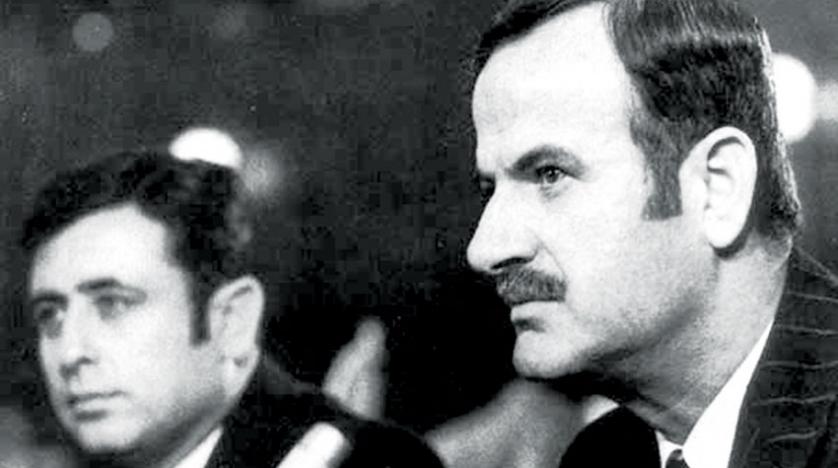

Former Syrian Vice President Abdul Halim Khaddam narrates in the eleventh and final episode of his memoirs published by “The Middle East” newspaper the details of the power struggle in Syria between 1966 and 1970. This struggle involved the Minister of Defense Hafez al-Assad and the Assistant Secretary General of the Ba’ath Party, Salah Jadid, as well as the preceding stages since the party took over the government. Additionally, it delves into his role in conveying “messages” from Assad to President Noureddine al-Atassi, who was aligned with Jadid.

Khaddam states that in November 1970, he went to the army command to meet with Assad and “suggested sending party branch secretaries from the military to Atassi to explain the situation, as he might believe that General Salah Jadid still held military power (…). They went to Atassi’s house, were received, and began discussing the crisis. He surprised them by deciding to expel them from the party, saying to them, ‘As the Secretary General of the party, I am expelling you.’ They left and informed Assad. On that day, the Qatari leadership members were arrested, including Jadid, Atassi, and others.” According to Khaddam, “Thus, one phase ended to pave the way for another. We gathered in the office of General Assad at the General Staff Headquarters in the evening, a group of party leaders, and we agreed to appoint Ahmed al-Khatib as the head of state, and General Assad as the Prime Minister. We set the next day for a meeting to appoint the ministers.”

Khaddam also reflects on his perception of changes in Assad’s stances, saying, “Assad believed that his words were correct, and what he said must be implemented. He was easily influenced by his family members… He always believed he was on the right path, and when he brought up a topic, he wouldn’t backtrack from it.”

After the Qatari leadership of the ruling Ba’ath Party resolved its conflict with the national leadership on February 23, 1966, it tightened its control over the country, adopting an extreme “Stalinist” approach and abandoning the core principles of the party that had advocated for freedom and democracy.

This approach led to widespread animosity among Syrians towards the party and its regime, causing a decline in the national economy. The regime resorted to repression and arrests to maintain control. During this period, small groups of influential Ba’athists from various provinces were formed, including myself, and personal direct contacts were established to prevent leaks to the leadership.

In that time frame, I visited Abdullah al-Ahmar and Nabih Hassan, each a party branch secretary, as well as the Minister of Labor, Mohammed Rabah al-Tawil. During the visit, al-Tawil initiated an attack on the leadership, joined by al-Ahmar and Hassan. I remained silent and occasionally criticized the minister, asking him, “Why are you attacking the leadership with us, and why don’t you express your opinions in the meetings?” After a few days, a party committee was formed to investigate us. These circumstances prompted us, as well as others, to search for a way to save the party.

In 1968, a party conference was held in Ya’fur near Damascus. During the military committee session of the conference, Defense Minister Hafez al-Assad proposed a project to establish a military front consisting of Syria, Jordan, and Iraq. The leadership opposed this proposal, considering dealing with Jordan not permissible as it was seen as an “American agent.” They also rejected cooperation with Iraq due to existing tensions between the two countries. Before the conference sessions concluded, Assad spoke and expressed views conflicting with the regime’s positions, including that the conflict with Israel “is not Syria’s conflict, but a conflict between all Arabs and Israel, and thus the differences with Arab countries must be overcome and they should be rallied for the conflict.” He then withdrew, followed by the military personnel, and the conference came to a halt.

Ibrahim Maakhous intervened and tried to persuade both the President of the State, Noureddine al-Atassi, and the Secretary-General of the party, Salah Jadid, and the Defense Minister to change their stances, proposing that Assad assume the position of Prime Minister while leaving the Defense Ministry. However, Assad rejected this proposal, and the campaigns between the two leadership teams escalated. During this phase, communications took place between us and Assad, and we agreed to convey to the people our convictions about their participation in power and changing the oppressive approach.

In late 1968, an extraordinary national conference was held at the Military Theater in Damascus. It was divided into two factions: the majority siding with the Qatari leadership, and the minority opposing it. I spoke at length during that conference, strongly criticizing the Qatari leadership and calling for a return to the core principles of the party, ensuring freedom and people’s participation. One of the comrades interrupted me, asking, “Why didn’t you speak like this in previous conferences?” I responded with an incident involving the Soviet Communist Party’s Secretary-General Nikita Khrushchev, who took power after Stalin’s death. Khrushchev criticized Stalin in a speech, prompting a party member to ask him, “Why didn’t you say that when Stalin was alive?” Khrushchev angrily took off his shoe and began hitting the table, exclaiming, “There are American spies in this conference. Now I will expose these spies.” Everyone fell silent. A few minutes later, Khrushchev said, “Do you see why I didn’t attack Stalin?”

After my speech, I faced a campaign from the supporters of the Qatari leadership, and the conference did not lead to a resolution of the crisis. Communications took place between al-Atassi and Assad, resulting in an agreement to form a new government with members from both the national and Qatari leaderships, aimed at cooling tensions and seeking solutions. Al-Atassi formed the government, which brought together members from both sides, and I was appointed Minister of Economy and Foreign Trade.

This government couldn’t solve the internal crises in the country or the party’s crisis, and matters worsened. The Qatari leadership decided to play its last cards, calling for a national conference to make decisions that would distance Assad from the party’s leadership and power. The conference was held in mid-November.

During the first session, the campaign against the Defense Minister intensified. We gathered in the office of General Naji Jamil (who Assad had transferred command of the Air Force to), and the meeting included Assad, Jamil, Mohammed Haydar, Azeddine Idrees, and myself. We discussed the conference’s situation, and I proposed writing a speech for Assad to deliver at the conference, containing principles that would inspire enthusiasm among Syrians, including granting freedoms, involving Syrians in power, and allowing party freedom and economic reforms. We agreed on these principles, and I, along with my comrades Haydar and Idrees, wrote them down and sent them to Assad. He read them during the second session, causing turmoil in the conference. Youssef Zu’ayn and Mustafa Rustum followed up the speech, endorsing its content, and the session was adjourned until the next day. On the following day, the Arab members left, and the conference’s sessions were not held.

Assad contacted me and asked me to visit him to discuss the situation. I went to his office, and the conversation began with him saying, “I don’t want to stage a military coup. I want to reform the party and the country.” We agreed that I would visit al-Atassi and discuss the situation with him to confirm that Assad had no intention of taking military action. Indeed, I went to al-Atassi’s house, where Dr. Mustafa Haddad was present. I explained what the Defense Minister had conveyed to me and told him, “You are the party’s Secretary-General, and it’s required of you to work towards resolving the crisis.” He reacted passionately, saying, “The crisis won’t end except by Assad and his officers leaving the country.” I replied, “Do you believe that such a decision is possible?” He said, “There is no other solution.” I responded, “Searching for a better solution is more productive than pushing matters towards a military resolution.” Dr. Haddad supported my point, but al-Atassi remained firm in his position. Zu’ayn intervened, tense, attempting to calm the situation, but emotions closed the doors.

I returned to the army command and informed Assad of the atmosphere. He expressed great frustration and asked me, “What should we do?” I suggested to him to send party branch secretaries, who were military personnel, to al-Atassi to explain the situation, as al-Atassi might believe that General Salah Jadid still had control over the army. Indeed, contact was made with the branch secretaries, and they were brought in by a private plane from their distant locations. After their arrival and meeting with General Assad, they went to al-Atassi’s house, where they were received. They began discussing the crisis with him, and he surprised them by deciding to expel them from the party, saying, “As the Secretary-General of the party, I am expelling you.” They left and informed Assad. On that day, the Qatari leadership members were arrested, including Jadid, al-Atassi, and others. Thus, one phase ended to pave the way for another.

We gathered in the evening at General Assad’s office at the General Staff Headquarters, a group of influential Ba’athists, and we agreed to appoint Ahmed al-Khatib as the head of state, and General Assad as the Prime Minister. We set the next day for a meeting to appoint the ministers.

On that day, I accompanied Assad to the Council of Ministers.

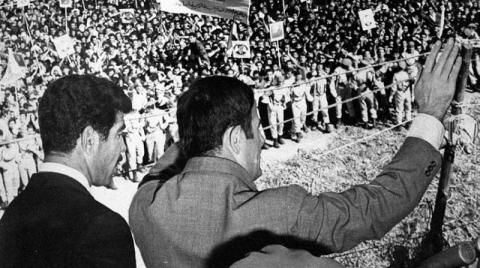

After assuming power and conducting visits to all the provinces, during which he received unprecedented receptions due to the difficult conditions prevalent during the Qatari leadership phase and the extremist approach it had taken in various areas of life, these visits solidified Assad’s perception of himself as “the beloved of the people.” He believed he could make the decisions he wanted and engage in work he believed in. As a result, a committee was formed to draft a new constitution.

This constitution was created, and it granted the President of the Republic unprecedented powers that had not been exercised by any democratic or dictatorial president. Article 91 stipulated, “The President of the Republic shall not be held accountable for the actions he performs in carrying out his duties except in cases of grand treason. The demand for his indictment shall be based on a proposal by at least one third of the members of the People’s Council and a decision by the People’s Council through an open vote and by the majority of two-thirds of its members in a special closed session. His trial shall only take place before the Supreme Constitutional Court.” In this article, the President cannot be accused of grand treason, even if it is apparent, due to the conditions specified making it impossible to make such accusations. Who would dare accuse a dictatorial president while he is in power?